The Best and Worst Books I Read in 2019

McCarthy, Melville, Sir Thomas Browne, and more

The Best

Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday

From the late 19th century to World War II, through the eyes of Stefan Zweig. From the stable order, prosperity, and peace of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to fratricidal wars, Weimar Germany, and Nazism. Mechanization, electrification, the breakdown of ossified social and political structures. Beautifully written and just incredibly sad and wistful. Zweig finished the manuscript in February 1942, posted it to his publisher, and killed himself the next day.

For I have indeed been torn from all my roots, even from the earth that nourished them, more entirely than most in our times. I was born in 1881 in the great and mighty empire of the Habsburg Monarchy, but you would look for it in vain on the map today; it has vanished without trace. I grew up in Vienna, an international metropolis for two thousand years, and had to steal away from it like a thief in the night before it was demoted to the status of a provincial German town. My literary work, in the language in which I wrote it, has been burnt to ashes in the country where my books made millions of readers their friends. So I belong nowhere now, I am a stranger or at the most a guest everywhere.

Leo Tolstoy, The Kreutzer Sonata

Chesterton wrote that Tolstoy pitied humanity not only for its pains, but also for its pleasures: "He weeps at the thought of hatred; but in The Kreutzer Sonata he weeps almost as much at the thought of love." Delightfully dark and cynical to an extreme degree—like a presentiment of Cioran in the form of a Russian moralist. Short, dense, and endlessly quotable.

And when one looks at our golden youth, at our officers, at those Parisians! And when all those gentlemen and myself, debauchees in our thirties with hundreds of the most varied and abominable crimes against women on our consciences, go into a drawing-room or a ballroom, well scrubbed, clean-shaven, perfumed, wearing immaculate linen, in evening dress or uniform, the very emblems of purity – aren’t we a charming sight?

Timur Kuran, Private Truths, Public Lies

This book is drier than the Sahara, but its insights on preference falsification are essential for understanding politics, public opinion, public discourse, and how governments control their subjects. How and why people present false opinions in public, how people try to influence this expression, epistemic and political effects. It's tough, but worth it: you will see the world through new eyes after reading it.

In Havel's own words, the crucial "line of conflict" thus ran not between the Party and the people but "through each person," for everyone was "both a victim and a supporter of the system."

Julien Gracq, Château d'Argol

An extraordinarily strange work that I initially didn't love, but grew to appreciate as I kept thinking about it for months and months. If you like Poe, Huysmans, Gustave Moreau, or surrealism, this is the book for you. A creepy castle, a dark forest, and lots of impenetrable symbols. Everything is somehow...suspended and quasi-magical, detached from the rules of everyday life. Gracq's elaborate style makes Lovecraft look like Hemingway and the translation is excellent.

A curious feature is the complete lack of dialogue. Instead, there are descriptions of conversations, which never touch on the subject but focus on the atmosphere and effects.

Herminien possessed the gift of penetrating the secrets of literature and art with subtle and perfect taste, revealing, however, their mechanism rather than all the power of the grace they contained.

Sir Thomas Browne, Hydriotaphia, Urne-Buriall, or, a Discourse of the Sepulchrall Urnes lately found in Norfolk

This classic essay from 1658 counts among its fans Borges, De Quincey, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Poe. Not so much for its contents, but rather for its style: endless sentences, over-the-top abuses of Latinate words, striking metaphors and imagery. It "smells in every word of the sepulchre", wrote Emerson. Browne begins by discussing an archaeological find in a dry, almost anthropological mode and then moves on to death, religion, burial rites, fame and infamy—all the while the style escalates to a wonderful Baroque crescendo in the final chapter.

There is no antidote against the Opium of time, which temporally considereth all things; Our Fathers finde their graves in our short memories, and sadly tell us how we may be buried in our Survivors. Grave-stones tell truth scarce fourty years: Generations passe while some trees stand, and old Families last not three Oaks. To be read by bare Inscriptions like many in Gruter, to hope for Eternity by Ænigmaticall Epithetes, or first letters of our names, to be studied by Antiquaries, who we were, and have new Names given us like many of the Mummies, are cold consolations unto the Students of perpetuity, even by everlasting Languages.

Max Frisch, Man in the Holocene

An experimental novella about knowledge, memory, and aging. Like a literary collage, I've never read anything like it. Frisch manages to evoke an overwhelming atmosphere of internal and external decay and collapse. Chaos and nature dismantling order. Man dies, the natural cycle continues.

While Geiser is wondering why he wanted a candle in the middle of the afternoon, he remembers having intended to seal a document, his final instructions in case anything happened. His resolve, as he searches for a pan, is to clean out his closet one of these days. But the pan, the little one, is already standing on the hot plate, the water in it bubbling, though the hot plate is no longer glowing. He forgot, while thinking about the untidiness of his closet and about his heirs, that he had already drunk his tea; the empty cup is warm, the tea bag dark and wet.

Michael Benson, Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece

Imagine the perfect book about the making of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Well, this is it. Exhaustive but never dull, it really manages to capture the Herculean nature of the accomplishment. The pictures are incredible.

Clarke even predicted to Kubrick, “This is the last big space film that won’t be made on location.”

Raymond Queneau, Exercises in Style

A very fun little book which I read based on Calvino's recommendation. A banal anecdote is repeated 99 times in 99 different styles ("botanical", "abusive", "dream", "animism", "apheresis", etc). It seems like it would get boring, but he really pulls it off. It's got a playful energy to it, and the concept sustains itself all the way through. Impressive translation, too.

Olfactory

In that meridian S, apart from the habitual smell, there was a smell of a beastly seedy ego, of effrontery, of jeering, of H-bombs, of a high jakes, of cakes and ale, of emanations, of opium, of curious ardent esquimos, of tumescent venal double-usurers, of extraordinary white zoosperms, there was a certain scent of long juvenile neck, a certain perspiration of plaited cord, a certain pungency of anger, a certain loose and constipated stench, which were so unmistakeable that when I passed the gare Saint-Lazare two hours later I recognised them and identified them in the cosmetic, modish and tailoresque perfume which emanated from a badly placed button.

Rutilius Claudius Namatianus, De Reditu Suo

A fascinating poem from the late Roman Empire. Rutilius was a high-ranking administrator from Gaul who still clung to paganism in an increasingly Christian empire. Rome had been sacked by Alaric in 410, and the poem was written 6 years after that. It describes Rutilius' journey from Rome back to his homeland. There's a Wolfeian dying world feel to it—they go by ship because the land route has been devastated by the invasion. Rutilius decries Christian ascetics hiding out from the world, though never losing hope that Rome will bounce back. Filled with all sorts of casual, mundane details that are usually left out from ancient accounts: annoying innkeepers, makeshift tents on the beach, meeting old friends.

Unfortunately the second half has been lost.

Each seventh day to shameful sloth's condemned,

Effeminate picture of a wearied god!

Their other fancies from the mart of lies

Methinks not even all boys could believe.

Would that Judea ne'er had been subdued

By Pompey's wars and under Titus' sway!

The plague's contagion all the wider spreads;

The conquered presses on the conquering race.

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale

Strange, experimental, at times Shakespearean, at times postmodern. Not even remotely flawless, but what book of this magnitude could be? Layers upon layers! Genuinely one of those "great, imperfect, torrential works, books that blaze a path into the unknown." America, God, capitalism, race, whiteness, literature, man vs nature, revenge, obsession, madness.

"Vengeance on a dumb brute!" cried Starbuck, "that simply smote thee from blindest instinct! Madness! To be enraged with a dumb thing, Captain Ahab, seems blasphemous."

"Hark ye yet again—the little lower layer. All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event—in the living act, the undoubted deed—there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask. If man will strike, strike through the mask! How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall? To me, the white whale is that wall, shoved near to me. Sometimes I think there's naught beyond. But 'tis enough. He tasks me; he heaps me; I see in him outrageous strength, with an inscrutable malice sinewing it. That inscrutable thing is chiefly what I hate; and be the white whale agent, or be the white whale principal, I will wreak that hate upon him. Talk not to me of blasphemy, man; I'd strike the sun if it insulted me. For could the sun do that, then could I do the other; since there is ever a sort of fair play herein, jealousy presiding over all creations. But not my master, man, is even that fair play.

W. Stanley Moss, Ill Met by Moonlight

Most World War II memoirs are filled with brutality, endless carnage, mud, ice, and/or burning tropical heat. This is a World War II memoir in the form of a bucolic comedy. A couple of charming and eccentric British officers (one was Moss, the other was famous travel writer Patrick Leigh Fermor) based in Egypt come up with the idea of abducting General Kreipe from Crete. They go to Crete, do a bit of spying, have a great time with the peasant guerrillas in the mountains drinking raki and wine, enjoying great food, and reading Baudelaire. Eventually they get to the general, which involves all sorts of daring deeds and close calls as the Nazis try to capture them and they try to escape back to Egypt. It's a fantastic (if somewhat juvenile) adventure all-round.

We are now hiding in a delightful spot which is about a quarter of a mile from Patsos. We sleep in a stone-walled hut which has been built against the base of a steep cliff, so with trees on three sides and the cliff behind us we could not have found a more sheltered position. Close at hand there is a waterfall, and all day long we hear the sound of water as it tumbles away, down and down into the valley. This sound seems to attract every bird in the neighbourhood, and from dawn till dusk we can hear nightingales singing in the trees around us. Nightingales seem mostly to sing in the day-time in Crete—but that’s Crete all over. “No sense of timing,” as Paddy has said.

Herman Melville, Bartleby, the Scrivener

The polar opposite of Moby-Dick in almost every way. This is one of those "perfect exercises of the great masters", short and flawless. Sloth, refusal, solitude, and negation.

I would prefer not to.

Michel Houellebecq, H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life

A very amusing essay, in that dry Houellebecqian way. Covers a lot of ground in very little space: Lovecraft's life, his themes, his style, critical reactions. Avoids the cheap psychologizing that many Lovecraft critics fall into. And reveals a lot about Houellebecq himself, too.

Lovecraft, in fact, hasn’t got the attitude of a novelist. Hardly any novelist of any description imagines that it is within his capacities to give an exhaustive depiction of life. Their mission is rather to “shed new light” on it; but given the facts themselves there is absolutely no choice. Sex, money, religion, technology, ideology, redistribution of wealth…a good novelist can’t ignore anything. And all this must take place within a coherent vision, grosso modo, of the world. Obviously the task is scarcely humanly possible, and the result almost always disappointing. A nasty profession.

Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian, or The Evening Redness in the West

Desolation, deserts, blood, mud, savagery, endless death, and senseless brutality. A lean and muscular style that goes perfectly with its subject matter. A Landian novel if there ever was one. The Judge is an incredible character who cuts straight to the darkest aspects of life, nature, and the universe as a whole. And what an unforgettable ending.

Whatever exists, he said. Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent. He looked about at the dark forest in which they were bivouacked. He nodded toward the specimens he’d collected. These anonymous creatures, he said, may seem little or nothing in the world. Yet the smallest crumb can devour us. Any smallest thing beneath yon rock out of men’s knowing. Only nature can enslave man and only when the existence of each last entity is routed out and made to stand naked before him will he be properly suzerain of the earth.

H. G. Wells, The Time Machine

I went into this one expecting a comfy Victorian adventure, instead I got a Nietzschean/Lovecraftian evolution-horror story about degeneration and the end of all life. Kind of falls apart towards the end, but it's a good read.

The brown and charred rags that hung from the sides of it, I presently recognized as the decaying vestiges of books. They had long since dropped to pieces, and every semblance of print had left them. But here and there were warped boards and cracked metallic clasps that told the tale well enough. Had I been a literary man I might, perhaps, have moralized upon the futility of all ambition. But as it was, the thing that struck me with keenest force was the enormous waste of labour to which this sombre wilderness of rotting paper testified.

The Worst

Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind

This collection of essays is filled with a series of baseless pronouncements on a bewildering array of topics: Bateson jumps from von Neumann's game theory to William Blake to learning and meta-learning to schizophrenia to anthropology to evolution to Freud to "the epistemology of cybernetics" to consciousness, all the time hinting that there is some sort of profound Grand Correspondence between them. But he never articulates it because no such correspondence actually exists.

Toward the end the book he drops even the pretense of rigour and just devolves into hippie ramblings about environmentalism and LSD, which feels like a fitting conclusion.

I personally do not believe that the dolphins have anything that a human linguist would call a “language.” I do not think that any animal without hands would be stupid enough to arrive at so outlandish a mode of communication.

Paul Feyerabend, Against Method

Some of the arguments Feyerabend makes are just bad in a normal way. He uses a series of post hoc ergo propter hoc arguments to push the idea that anti-scientific methods were necessary for scientific progress (counterfactuals? what are those?). He argues that alternatives to a theory must always precede the detection of anomalies, despite a million different counterexamples in the history of science.

At other times his arguments are bad in a theatrical, spectacular, absurd way. For example when he says that the Catholic church was right to suppress Galileo because he threatened social harmony, or when he praises Mao's Cultural Revolution (when universities were closed and scientists were sent to do manual labor in fields and factories) for "improving the practice of medicine". Feyerabend somehow simultaneously argues in favor of totalitarian government control of science and "methodological anarchism". He never seems to notice the contradiction.

Of course, our well-conditioned materialistic contemporaries are liable to burst with excitement over events such as the moonshots, the double helix, non-equilibrium thermodynamics. But let us look at the matter from a different point of view, and it becomes a ridiculous exercise in futility. It needed billions of dollars, thousands of well-trained assistants, years of hard work to enable some inarticulate and rather limited contemporaries to perform a few graceless hops in a place nobody in his right mind would think of visiting - a dried out, airless, hot stone. But mystics, using only their minds, travelled across the celestial spheres to God himself, whom they viewed in all his splendour, receiving strength for continuing their lives and enlightenment for themselves and their fellow men. It is only the illiteracy of the general public and of their stem trainers, the intellectuals, and their amazing lack of imagination that makes them reject such comparisons without further ado.

Benjamin Noys, Malign Velocities: Accelerationism & Capitalism

This book is written at the intellectual level of a youtube comment. Noys ignores Land because he thinks a critique of his work would be "superfluous", which is a bit like me dismissing Roger Federer as a tennis player by saying that a game between us would be superfluous. Bad history, worse economics, and filled with endless whining.

The relative lack of commodities – at first glance anti-pleasure – would actually allow for a less extreme division of labor, freeing one from illusory ‘choices’ and the mental overload of advertising, as well as a greater (if not absolute) freedom from the tyranny of things.

Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World

Whitehead co-wrote Principia Mathematica with Russell. Whitehead was Quine's thesis advisor. Yet this book comes across as the ramblings of a hippie who took one too many hits of LSD. A bizarre attempt to counter materialism and replace it with a cooky pantheistic metaphysics where everything perceives everything else ("For Berkeley's mind I substitute a process of prehensive unification") and events happen multiple times in multiple locations because things perceive each other. God, religion, social progress, science, environmentalism, art...my notes for this book are just filled from top to bottom with question marks.

Cognition is the emergence, into some measure of individualised reality, of the general substratum of activity, poising before itself possibility, actuality, and purpose.

Eric Voegelin, Science, Politics and Gnosticism

Science, Politics and Gnosticism is basically this tweet in book form:

The shit he was on about at the time was gnosticism, on which he blames everything bad from Nietzsche and Hobbes to Hegel and Marx. Ultimately gnosticism has very little to do with the point being made, and that point is preposterous and badly argued. Anyone going into this not already believing in God is just wasting their time, as Voegelin is only interested in preaching to the choir.

A second complex of symbols that runs through modern gnostic mass movements was created in the speculation on history of Joachim of Flora at the end of the twelfth century.

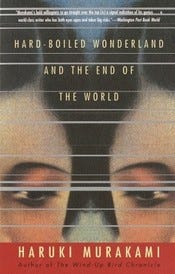

Haruki Murakami, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World

I loved the first chapter, thinking it was stand-alone. Imagine if it had no follow-up, just a guy in an elevator and then a long walk. Fantastically crazy. But then the rest of the novel happens. I'm not entirely sure what I was expecting with this one, but I had the impression that Murakami was...good? This is sub-pulp garbage. Murakami is a Kmart P K Dick, and Dick's not exactly highbrow to begin with.

The SF bits are not really SF, they're fantasy papered-over with a bit of technospeak. Despite this there are endless, meaningless, tedious infodumps. What could possibly be the point of an infodump about a nonsensical and arbitrary system of magic? And what's the deal with all the chicks being desperately thirsty for the protagonist's cock? It's like something out of an extremely bad harem anime, yet it doesn't appear to be ironic.