Book Review: The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

A collection of over 180 biographies of Renaissance artists

I found Giorgio Vasari through Burckhardt1 and Barzun. The latter writes: "Vasari, impelled by the unexampled artistic outburst of his time, divided his energies between his profession of painter and builder in Florence and biographer of the modern masters in the three great arts of design. His huge collection of Lives, which is a delight to read as well as a unique source of cultural history, was an amazing performance in an age that lacked organized means of research. [...] Throughout, Vasari makes sure that his reader will appreciate the enhanced human powers shown in the works that he calls "good painting" in parallel with "good letters.""

Vasari was mainly a painter, but also worked as an architect. He was not the greatest artist in the world, but he had a knack for ingratiating himself with the rich and powerful, so his career was quite successful. Besides painting, he also cared a lot about conservation: both the physical preservation of works and the conceptual preservation of the fame and biographies of artists. He gave a kind of immortality to many lost paintings and sculptures by describing them to us in his book.

His Lives are a collection of more than 180 biographies of Italian artists, starting with Cimabue (1240-1302) and reaching a climax with Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564). They're an invaluable resource, as there is very little information available about these people other than his book; his biography of Botticelli is 8 pages long, yet on Botticelli's wikipedia page, Vasari is mentioned 36 times.

He was a straight-laced man surrounded on all sides by wild and eccentric artists. While Vasari was a sober businessman, always delivering his work on time, the people he was writing about were usually tempestuous madmen who would take commissions and leave the work unfinished, or go off on the slightest affront and start hacking apart their own works. Even of the great Leonardo he writes that "through his comprehension of art, [he] began many things and never finished one of them".

The greater part of the craftsmen who had lived up to that time had received from nature a certain element of savagery and madness, which, besides making them strange and eccentric, had brought it about that very often there was revealed in them rather the obscure darkness of vice than the brightness and splendour of those virtues that make men immortal.

Many of them were undone by their love of food, drink, and/or women:

...when his dear friend Agostino Chigi commissioned him to paint the first loggia in his palace, Raffaello was not able to give much attention to his work, on account of the love that he had for his mistress.

Gwern's review of the autobiography of Cellini (which includes the words "aside from the demonology and weather-controlling") should give you a taste of what these guys were like.

Arnold M. Ludwig, The Price of Greatness: Resolving the Creativity and Madness Controversy

Vasari's approach to the truth can be described as loose, if not gossipy. Many of the lives include fabricated elements, sometimes obviously so: I doubt anyone ever believed the story of Cimabue taking on Giotto as a pupil after seeing him scratch a painting on a stone. One of the most striking tales is the murder of Domenico Veneziano by Andrea del Castagno, but in reality Castagno actually died first. Vasari also damaged the reputation of some of his competitors, such as Jacopo da Pontormo, whom he portrayed as a paranoid recluse.

Vasari is also hilariously biased in favor of Florence: "in the practice of these rare exercises and arts—namely, in painting, in sculpture, and in architecture—the Tuscan intellects have always been exalted and raised high above all others". The story of his visit to Titian (a Venetian) is typical:

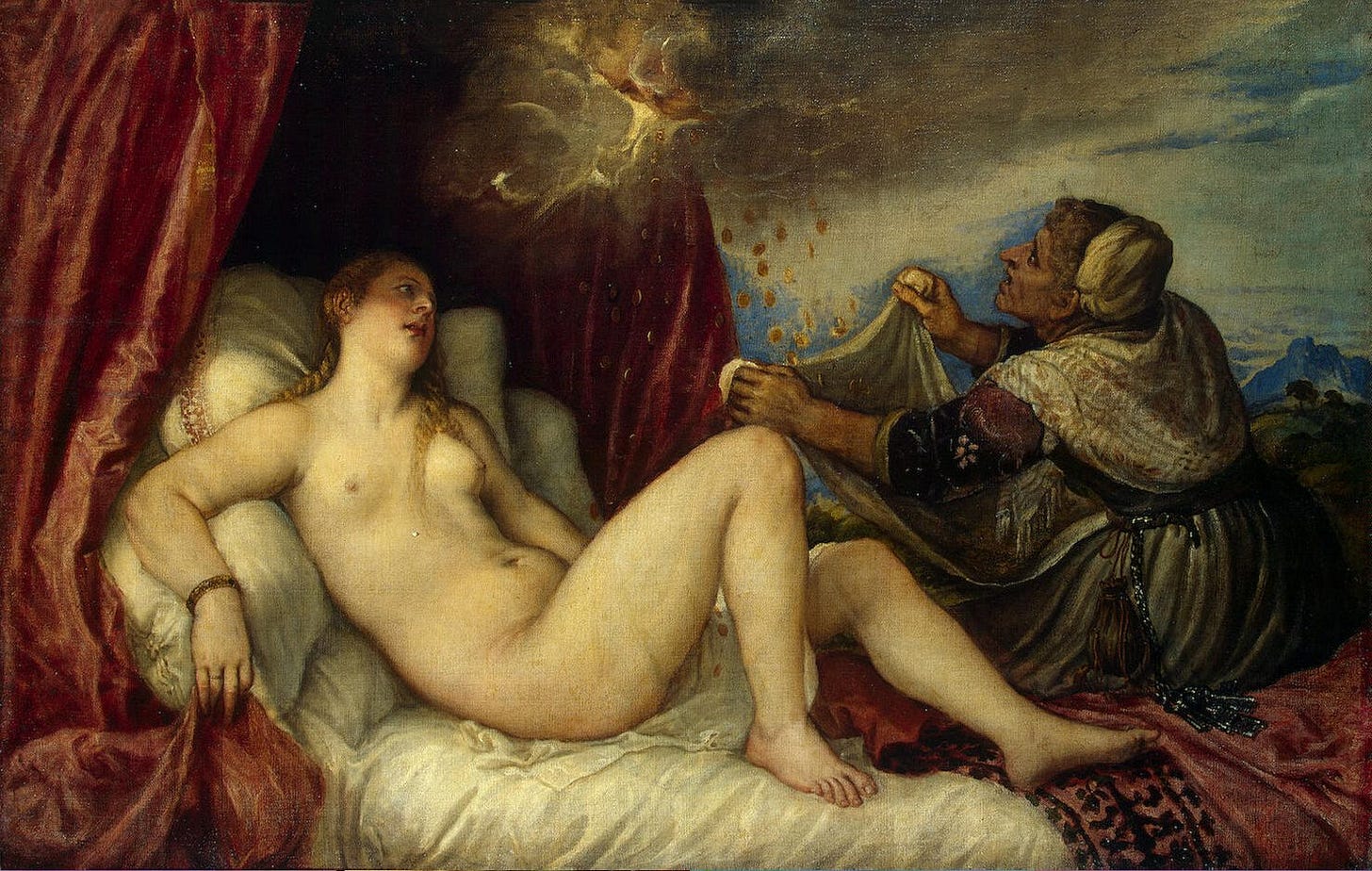

One day as Michelangelo and Vasari were going to see Titian in the Belvedere, they saw in a painting he had just completed a naked woman representing Danae with Jupiter transformed into a golden shower on her lap, and, as is done in the artisan's presence, they gave it high praise. After leaving Titian, and discussing his method, Buonarroti strongly commended him, declaring that he liked his colouring and style very much but that it was a pity artisans in Venice did not learn to draw well from the beginning and that Venetian painters did not have a better method of study.

Titian, Danae with Jupiter as a "golden shower"

I read (as usual) the Everyman edition, but would not recommend braving the entire work unless you're a Renaissance art fanatic. The collection spans over 2000 pages, and can get tiresome and repetitive when you go through the 100th similar biography of some minor painter you've never heard of. I would, however, recommend the best chapters which I have picked out below (and which are freely available online):

Giotto (1267-1337), an early stepping stone between the medieval "Greek style" and the modern one.

Uccello (1397-1475), the pioneer of perspective.

Piero di Cosimo (1462-1522), an eccentric who was influenced by the Dutch and eventually fell under the sway of Savonarola.

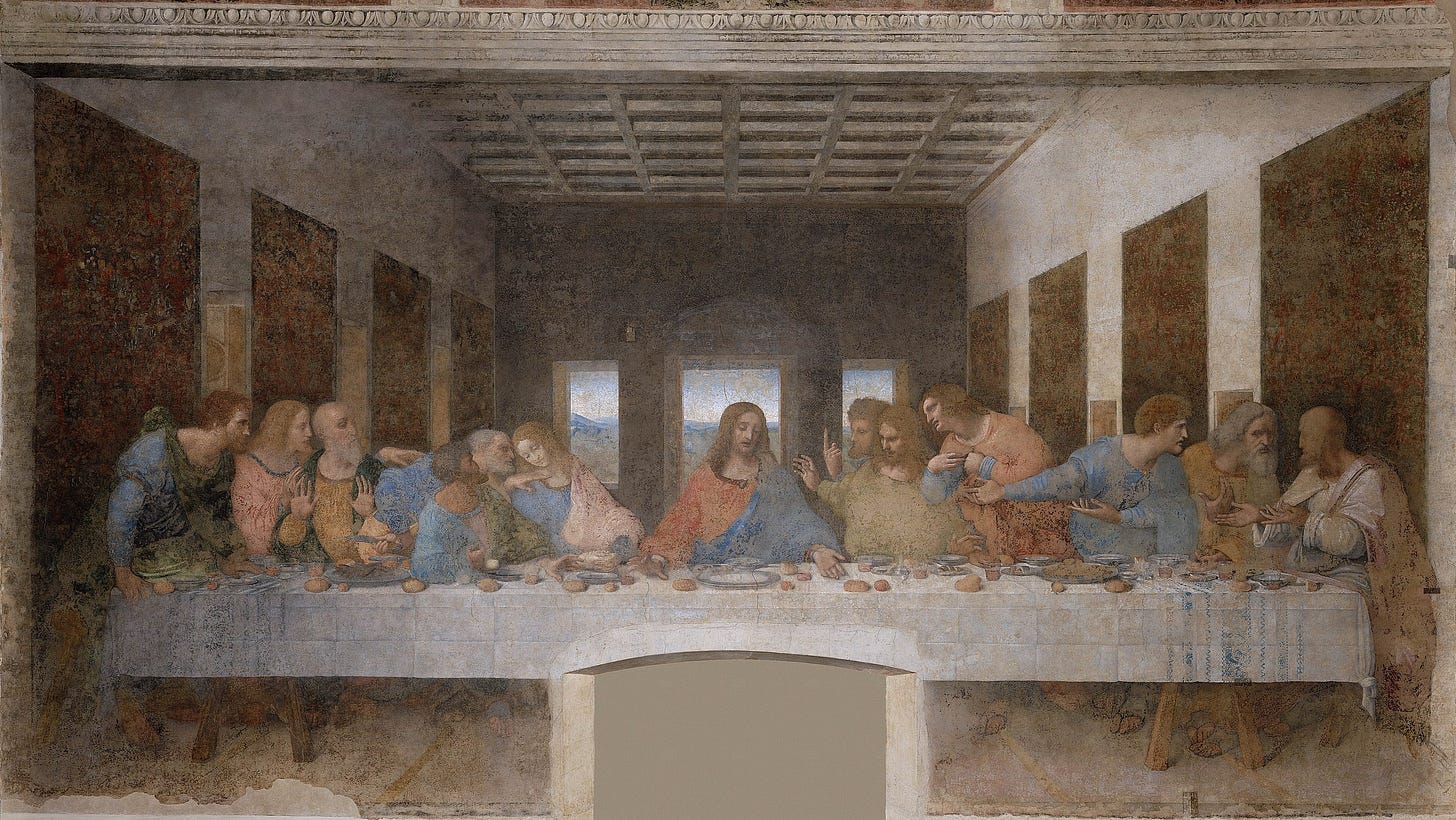

Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519), you've probably heard of him.

Raffaello (1483-1520), a brilliant talent who died young.

Il Rosso (1495-1540), who travelled to France and painted for Francis I.

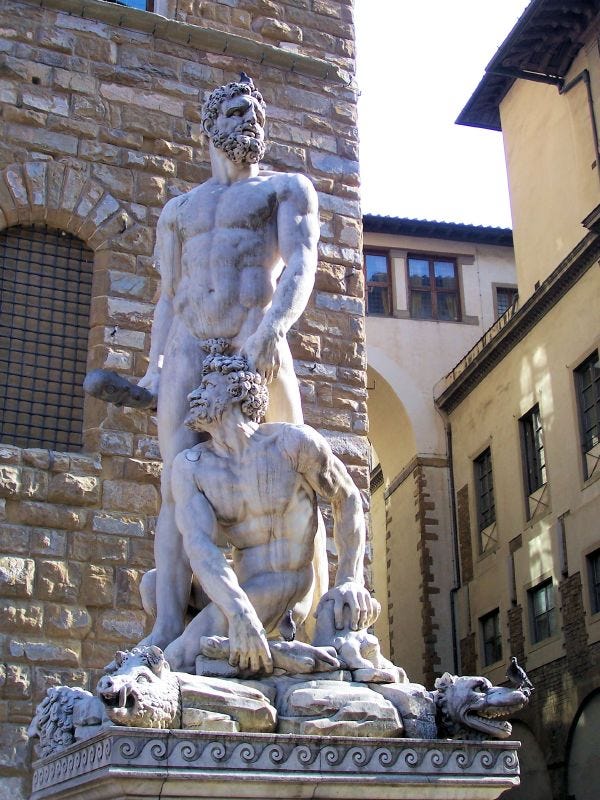

Baccio Bandinelli (1493-1560), who everyone hated.

Il Sodoma (1477-1549), the name says it all. Had a pet monkey.

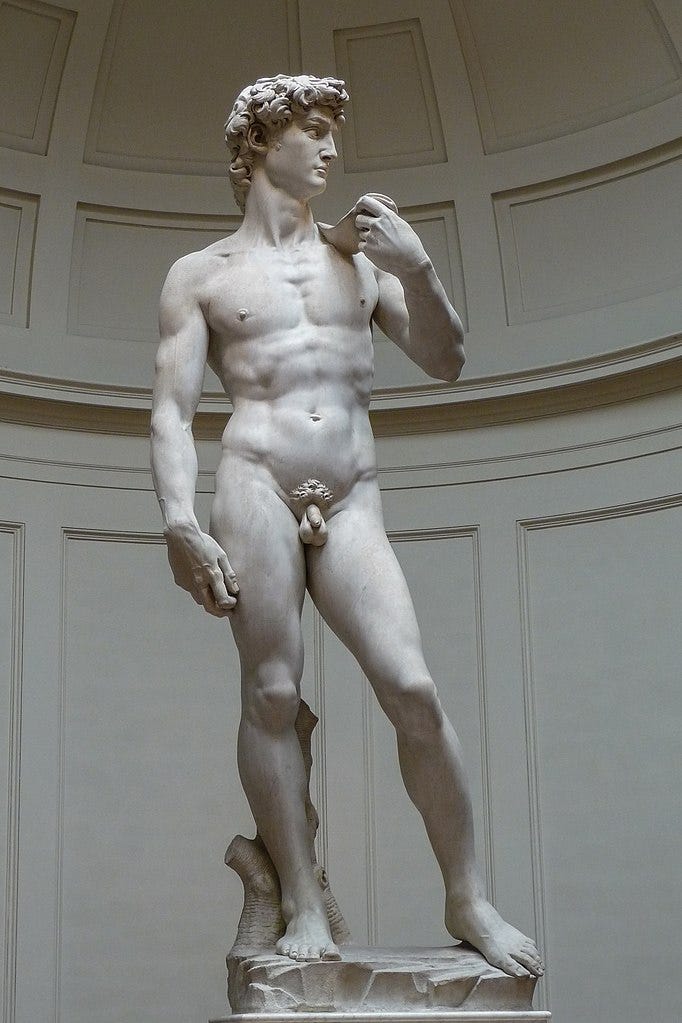

Michelangelo (1475-1564), Il Divino.

The Golden Present

Giorgio Vasari was one of the earliest philosophers of progress. Petrarch (1304-1374) invented the idea of the dark ages in order to explain the deficiencies of his own time relative to the ancients, and dreamt of a better future:

My fate is to live among varied and confusing storms. But for you perhaps, if as I hope and wish you will live long after me, there will follow a better age. This sleep of forgetfulness will not last forever. When the darkness has been dispersed, our descendants can come again in the former pure radiance.

To this scheme of ancient glory and medieval darkness, Vasari added a third—modern—age and gave it a name: rinascita.2 And within his rinascita, Vasari described an upward trajectory starting with Cimabue, and ending in a golden age beginning with eccentric Leonardo and crazed sex maniac Raphael, only to give way to the perfect Michelangelo in the end. It is a trajectory driven by the modern conception of the artist as an individual auteur, rather than a faceless craftsman.

The most benign Ruler of Heaven in His clemency turned His eyes to the earth, and, having perceived the infinite vanity of all those labours, the ardent studies without any fruit, and the presumptuous self-sufficiency of men, which is even further removed from truth than is darkness from light, and desiring to deliver us from such great errors, became minded to send down to earth a spirit with universal ability in every art and every profession.

This golden age was certainly no utopia, as 16th century Italy was ravaged by political turbulence, frequent plague, and incessant war. Many of the artists mentioned were at some point taken hostage by invading armies; Vasari himself had to rescue a part of Michelangelo's David when it was broken off in the battle to expel the Medici from Florence.

And yet Vasari saw greatness in his time, and the entire book is structured around a narrative of artistic progress. He documented the spread of new technologies and techniques (such as the spread of oil painting, imported from the Low Countries), which—as an artist—he had an intimate understanding of.

This story of progress is paralleled with the rediscovery (and, ultimately, surpassing) of the ancients. It would take until the 17th century for the querelle des Anciens et des Modernes to really take off in France, but in Florence Vasari had already seen enough to decide the question in favor of his contemporaries—the essence of the Enlightenment is already present in 1550. He writes about Donatello (1386-1466), who produced the first nude male sculpture of the modern era:

The talent of Donato was such, and he was so admirable in all his actions, that he may be said to have been one of the first to give light, by his practice, judgment, and knowledge, to the art of sculpture and of good design among the moderns; and he deserves all the more commendation, because in his day, apart from the columns, sarcophagi, and triumphal arches, there were no antiquities revealed above the earth. And it was through him, chiefly, that there arose in Cosimo de' Medici the desire to introduce into Florence the antiquities that were and are in the house of the Medici; all of which he restored with his own hand.

Similarly, he explains that Mino da Fiesole's (1429-1484) work was "somewhat stiff", yet it was nonetheless admired because "few antiquities had been discovered up to that time". The ancients created a new higher standard, which first created a thirst for imitation, then an impetus to outclass it.

...their successors were enabled to attain to it through seeing excavated out of the earth certain antiquities cited by Pliny as amongst the most famous, such as the Laocoon, the Hercules, the Great Torso of the Belvedere, and likewise the Venus, the Cleopatra, the Apollo, and an endless number of others, which, both with their sweetness and their severity, with their fleshy roundness copied from the greatest beauties of nature, and with certain attitudes which involve no distortion of the whole figure but only a movement of certain parts, and are revealed with a most perfect grace, brought about the disappearance of a certain dryness, hardness, and sharpness of manner...

It is curious that this competitive attitude seems to have disappeared in later eras. In the 18th century, for example, the English painter Joshua Reynolds said of the Belvedere Torso that it retained "the traces of superlative genius…on which succeeding ages can only gaze with inadequate admiration." The Italians of the Renaissance had such a civilizational confidence and such an individual lust for Glory that these fatalistic thoughts would never enter their minds. Take Raphael's School of Athens for example: imagine the self-confidence (if not presumption) necessary to paint Plato (portrayed by da Vinci) and Heraclitus (portrayed by Michelangelo) in the form of your friends and contemporaries! Imagine someone trying that today—Dennet as Plato, Gaspar Noé as...Diogenes?

What came first, the excellence or the confidence? Who can disentangle cause and effect? Braudel suggests an initial "restlessness" created the necessary conditions:

Perhaps if the door is to be opened to innovation, the source of all progress, there must be first some restlessness which may express itself in such trifles as dress, the shape of shoes and hairstyles?

Vasari certainly thought this ambition was a necessary ingredient for greatness. Commenting on Andrea del Sarto, he writes that he was excellent in all skills but "a certain timidity of spirit and a sort of humility and simplicity in his nature made it impossible that there should be seen in him that glowing ardour and that boldness which, added to his other qualities, would have made him truly divine in painting".

And one may ask: why is there no ancient Vasari? Pliny, describing the Laocoön, writes that it is "a work to be preferred to all that the arts of painting and sculpture have produced". Yet he is content to simply mention the names of the artists in passing: Agesander, Athenodorus, and Polydorus of Rhodes. There is not the slightest hint of curiosity about the lives of those most excellent men. Even worse, they were (highly-skilled) copyists, selling reproductions of Hellenistic works to wealthy Romans. The name of the original sculptor is lost to time.3

Aesthetic Value Over Time

You're probably familiar with the story of the Mona Lisa: it was unpopular until it was stolen in 1911, Apollinaire and Picasso were suspects in the case, and when it was finally returned two years later it had become the most famous painting in the world. I was surprised, then, to see that the Mona Lisa was singled out for effusive praise by Vasari. He even focuses on that famous smile:

For Francesco del Giocondo, Leonardo undertook the portrait of Mona Lisa, his wife, and after working on it for four years, he left the work unfinished, and it may be found at Fontainebleau today in the possession of King Francis. Anyone wishing to see the degree to which art can imitate Nature can easily understand this from the head, for here Leonardo reproduced all the details that can be painted with subtlety. The eyes have the lustre and moisture always seen in living people, while around them are the lashes and all the reddish tones which cannot be produced without the greatest care. The eyebrows could not be more natural, for they represent the way the hair grows in the skin—thicker in some places and thinner in others, following the pores of the skin. The nose seems lifelike with its beautiful pink and tender nostrils. The mouth, with its opening joining the red of the lips to the flesh of the face, seemed to be real flesh rather than paint. Anyone who looked very attentively at the hollow of her throat would see her pulse beating: to tell the truth, it can be said that portrait was painted in a way that would cause every brave artist to tremble and fear, whoever he might be. Since Mona Lisa was very beautiful, Leonardo employed this technique: while he was painting her portrait, he had musicians who played or sang and clowns who would always make her merry in order to drive away her melancholy, which painting often brings to portraits. And in this portrait by Leonardo, there is a smile so pleasing that it seems more divine than human, and it was considered a wondrous thing that it was as lively as the smile of the living original.

There are, however, one or two minor problems with his account. One of them is that Vasari never actually saw the Mona Lisa: he was about 6 years old when the painting was moved to France, and he never left Italy. Vasari also says that Leonardo left the painting unfinished, while the Mona Lisa is very much finished. So what's going on? Until the 20th century people simply thought he made it up based on sketches or second-hand accounts.

And then, in 1913, an art collector discovered a second Mona Lisa hanging in a house in Somerset. By all accounts it appears to be authentic, and it matches a sketch by Raphael. It's also a better match for Vasari's description, though he may not have seen this one either. If he thought this one was great, just imagine how he would have raved about the first Mona Lisa!

The Second Mona Lisa

This raises the question: do we venerate the same paintings as Vasari due to path dependency, or due to constancy in aesthetic judgment? Broadly, Vasari's taste is our own. He likes Raphael, da Vinci, and Michelangelo above all others. There are certainly those who argue that the influence and worship of Florentine artists is merely a historical accident, and if Vasari had been a Venetian the history of painting would have turned out rather different.

There are a few interesting points of difference. For example, Botticelli only gets a very short biography, and his Birth of Venus merits not more more than a passing comment: Vasari says "he expressed himself with grace". Another artist who was mostly ignored by Vasari and was later "reevaluated" is the highly erotic Antonio da Correggio.

Correggio, Jupiter and Io

Architecture?

YOU - Hold on, is architecture also art?

CONCEPTUALIZATION - Of course not, it's autism. Box-drawing. Masturbation with a ruler and a sextant or whatever they use.

Painters, naturally. Sculptors, of course. But...architects? Certainly no twenty-first century chronicler would collect the lives of painters, sculptors, and architects. In our own age architecture is little more than an exercise in applied misanthropy. It has gotten so bad even the commies can tell it sucks, and they're not exactly famous for their aesthetic discernment. And these Renaissance artists were not limited to constructing fancy villas or churches, they often got involved in military engineering as well!

Architects might try to defend themselves by appealing to specialization and saying that, as the science has progressed, an architect today requires far more specialized knowledge than they did in the 16th century. One cannot be both a painter and an architect at the same time. Yet I cannot help but notice that the Duomo and the Uffizi are still beautiful and still standing, while our contemporary concrete claptrap starts crumbling after a couple of years. Our segregation of these fields is both arbitrary and misguided. Perhaps education (and the way it commoditizes knowledge) is to blame.4

Human Capital, Power Laws, and Cluster Effects

Perhaps the reason these people were able to paint, sculpt, architect, and sometimes even do a bit of military engineering on the side, is that art was one of very few avenues available at the time for people to monetize their high human capital. A smart guy in 16th century Florence had limited options: he might go into law, try to be a scribe, or (if he had money) commerce. Science was not a profession, and there were no hedge funds or startups. Art offered a new avenue, open to all with talent.5

Art was also something of a winner-take-all market, with virtually unlimited upside for the select few who could make it to the top. Like modern athletes, the superstars were drowning in money while the average painter didn't make all that much. Time seems to have confirmed this power law in artistic excellence: nobody goes to a museum for the paintings of Bartolomeo Vivarini, while da Vinci draws millions every year.

Societies are broadly defined by how they allocate status and (by extension) how they allocate the scarce biological resources they have access to. Rome rewarded military leadership, so it got a lot of great generals (and civil wars). The kleptocrats of Renaissance Italy allocated talent to art; gold and fame attracted competence. At the time Vasari was writing, there were about thirty thousand men in Florence—roughly the same as the number of male citizens in Classical Athens, and also roughly the same as today's population of Dubuque, Iowa. Yet their achievements (to borrow a phrase from Gibbon) would excuse the computation of imaginary millions.

One might ask: where are all the Shakespeares? There are about 25x more literate men in England today than in 1564, how come we aren't producing 25x more Shakespeares? The answer is that our society does not allocate much of its human capital to playwriting. There are (potentially) great authors who spend 8 hours a day writing ads for cereal, or improving trading algorithms by 0.01%. Capitalism, for all its virtues, tends to instill a preference for mere optimization in its subjects; the shadow of utility blots out the impetus for Glory.

One of the starkest lessons from Vasari is the importance of clusters in artistic production. He highlights both the spur of competition and the virtues of learning through imitation. He documents how new techniques (oil, perspective, new approaches to color) spread like wildfire, and how the newly unearthed Roman statues provided both a lesson and a stimulus for improvement. The mentor-mentee relationship was extremely important; a young artist could destroy his entire career by choosing the wrong master.

There is an extensive literature in "economics"6 covering the influence of agglomeration in creative industries. Hollywood is an obvious example, but there also seem to be agglomeration gains in 18-19th century classical music, while a writer who moved to London in the 18th or 19th century ended up with 12% higher productivity. Renaissance Florence certainly seems to be another one of these (which suggests an element of path dependency).

A century ago a man like Ernest Hemingway could just travel to Paris, join a flourishing artistic community, and have lunch with the world's greatest author (James Joyce). Imagine some random guy flying to New York and trying to have a meal with Thomas Pynchon today. Global connectivity has made us more insular by removing the barriers that used to act as filters. The apprenticeship opportunities of the Renaissance do not exist any more, though the wealthy patrons are still around.

Yet new possibilities for cluster formation open up on the internet: group chats, forums, perhaps even twitter. But it is not easy to cultivate the right mix of competition and imitation, or the preconditions necessary for cultural confidence and a lust for Glory. Perhaps the closest analogy in our time would be Silicon Valley; a relatively small area which attracts talent in search of money and fame. It certainly has that culture of ambition.

I leave you with a final quotation from Vasari, on the motivations behind art and how they affect the ultimate product:

And, to tell the truth of the matter, those craftsmen who have as their ultimate and principal end gain and profit, and not honour and glory, rarely become very excellent, even although they may have good and beautiful genius; besides which, labouring for a livelihood, as very many do who are weighed down by poverty and their families, and working not by inclination, when the mind and the will are drawn to it, but by necessity from morning till night, is a life not for men who have honour and glory as their aim, but for hacks, as they are called, and manual labourers, for the reason that good works do not get done without first having been well considered for a long time. And it was on that account that Rustici used to say in his more mature years that you must first think, then make your sketches, and after that your designs; which done, you must put them aside for weeks and even months without looking at them, and then, choosing the best, put them into execution; but that method cannot be followed by everyone, nor do those use it who labour only for gain.

Giorgio Vasari, Self-portrait

"And without Giorgio Vasari of Arezzo and his all-important work, we should perhaps to this day have no history of northern art, or of the art of modern Europe, at all."

The word "renaissance" was only popularized in the 19th century by Michelet.

There was a sculptor-biographer named Xenokrates of Sicyon but all his works are lost.

McKenzie Wark: "Education “disciplines” knowledge, segregating it into homogenous “fields,” presided over by suitably “qualified” guardians charged with policing its representations. The production of abstraction both within these fields and across their borders is managed in the interests of preserving hierarchy and prestige. Desires that might give rise to a robust testing and challenging of new abstractions is channelled into the hankering for recognition."

Michelangelo would undoubtedly have scored very well on the GRE.

All will be trampled under the steady imperial advance of the economists.